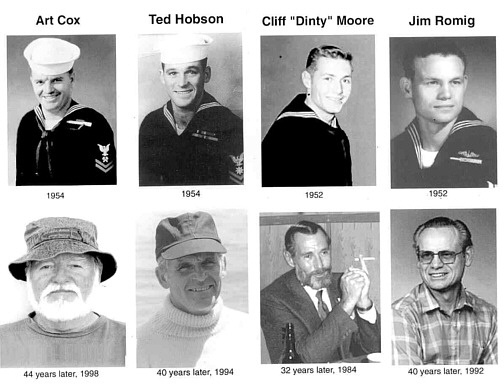

In the California town of Ventura during 1950, activities of those in their late teens centered around Merle’s Drive-In. Among them were Ted Hobson and Jim Romig (l-r, above left). Life was uncomplicated for them at this time, but changes were on the way. Above right is the middle of the line for the 1950 Ventura Junior College Pirates. The right guard is Romig, the left guard is Hobson and in the middle, at center, is Russ Goldman–a marine reservist. The North Koreans had invaded the South during the previous summer, but Jim and Ted thought little of it until the week before the fourth game. That is when Russ was called to active duty, and he was just the first of a number of teammates that, as reservists and members of the National Guard, left the team for active duty before the football season ended. By then the conflict in Korea was on all of their minds. Ted was particularly concerned because he had spent more time with football than with studies and knew that his grades made him a prime candidate for the Draft. Then one Friday during early December, he made the mistake of asking the local Draft Board when he could expect to be called. The Draft Board representative was surprised that he had not been called weeks before, and informed him he could expect to be inducted into the Army within a few days.

In the California town of Ventura during 1950, activities of those in their late teens centered around Merle’s Drive-In. Among them were Ted Hobson and Jim Romig (l-r, above left). Life was uncomplicated for them at this time, but changes were on the way. Above right is the middle of the line for the 1950 Ventura Junior College Pirates. The right guard is Romig, the left guard is Hobson and in the middle, at center, is Russ Goldman–a marine reservist. The North Koreans had invaded the South during the previous summer, but Jim and Ted thought little of it until the week before the fourth game. That is when Russ was called to active duty, and he was just the first of a number of teammates that, as reservists and members of the National Guard, left the team for active duty before the football season ended. By then the conflict in Korea was on all of their minds. Ted was particularly concerned because he had spent more time with football than with studies and knew that his grades made him a prime candidate for the Draft. Then one Friday during early December, he made the mistake of asking the local Draft Board when he could expect to be called. The Draft Board representative was surprised that he had not been called weeks before, and informed him he could expect to be inducted into the Army within a few days.

This development was not totally unexpected; in fact, Ted had already discussed options with the local Navy recruiter and had asked Jim whether he’d be interested in the Navy. Jim agreed that enlisting in the Navy was the way to go, and they approached two of Jim’s high-school buddies with the same proposition. Dinty Moore was at that time working in an oil field in Montebello, near Los Angeles, while Buck Buchanan was working on his family’s farm on the outskirts of Ventura. Both had played football with Jim during all four years at Ventura high school, while Ted had captained the Oxnard Yellowjackets, their arch rivals. Neither was enrolled as a student, which made them vulnerable to the Draft, and they wanted to avoid the Army. Dinty jumped at the chance to enlist in the Navy with Jim and Ted, but Buck had already decided to join the Marines. (Buck’s choice proved tragic, as little more than a year later he was killed by a Chinese mortar on a Korean mountain side. There is a tribute to Buck, written by Romig, at the Korean War Web site. http://www.koreanwar.org/html/korean_war_project_remembrance_1.html?KCCFADD__CASUALTY_ID=2796 )

Although it was early in December when Jim, Ted and Dinty signed up at the Navy Recruiting Office, their induction was deferred until after Christmas. It was before dawn on the morning of 27 December 1950 when they boarded the bus in downtown Ventura that would take them to the Navy Induction Center in Los Angeles. Also boarding that bus was Art Cox, who they did not know at the time, but who would share experiences with them over the coming years.

Although it was early in December when Jim, Ted and Dinty signed up at the Navy Recruiting Office, their induction was deferred until after Christmas. It was before dawn on the morning of 27 December 1950 when they boarded the bus in downtown Ventura that would take them to the Navy Induction Center in Los Angeles. Also boarding that bus was Art Cox, who they did not know at the time, but who would share experiences with them over the coming years.

The Navy Experience Begins

The recruits arrived at the Naval Training Center, San Diego, in civilian clothes, but by day’s end they were in sailor dungarees.

The recruits arrived at the Naval Training Center, San Diego, in civilian clothes, but by day’s end they were in sailor dungarees.

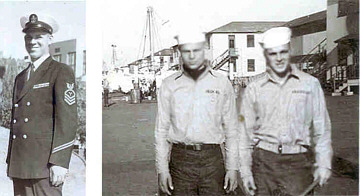

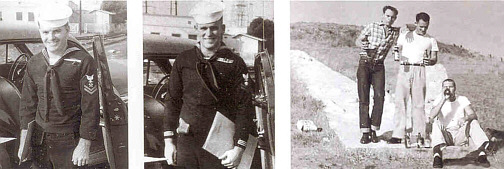

Chief E. Bojnowski guided Company 614 through Boot Camp. On the right, Seaman Recruits Romig and Hobson get used to a new world. They and Cox were together in Company 614, while Moore had been assigned to Company 615.

Chief E. Bojnowski guided Company 614 through Boot Camp. On the right, Seaman Recruits Romig and Hobson get used to a new world. They and Cox were together in Company 614, while Moore had been assigned to Company 615.

Training in Boot Camp began with emphasis on working as a unit rather than as an individual. Company 614 performed all daily tasks as a group, as at left, below, where they line up for chow after marching to the mess hall. Preparation for life aboard ship also involved giving up any semblance of privacy that might have been important as a civilian (right). This photo shows Boot Camp to be a transition, as aboard ship there will be no partitions.

Foremost in preparation for the crowded conditions to be experienced aboard ship was acquiring an appreciation for cleanliness. Much of Boot Camp was spent scrubbing clothes. In the photo below, center, Art Cox and Jim Romig are securing their wash to drying lines. (At far left in that photo is Jim Flot, who will later be a Rochester shipmate). This exercise involved meticulous attachments using tiny bits of line, a procedure that was in itself training in neatness (and even line-handling). As illustrated in the photo on the right, some recruits resisted the notion of personal cleanliness. In this instance, personalized instruction administered by shipmates after hours provides a valuable lesson (an example of “tough love” many years before this term became popular).

Foremost in preparation for the crowded conditions to be experienced aboard ship was acquiring an appreciation for cleanliness. Much of Boot Camp was spent scrubbing clothes. In the photo below, center, Art Cox and Jim Romig are securing their wash to drying lines. (At far left in that photo is Jim Flot, who will later be a Rochester shipmate). This exercise involved meticulous attachments using tiny bits of line, a procedure that was in itself training in neatness (and even line-handling). As illustrated in the photo on the right, some recruits resisted the notion of personal cleanliness. In this instance, personalized instruction administered by shipmates after hours provides a valuable lesson (an example of “tough love” many years before this term became popular).

The first navy liberty came after three weeks of training. Turned loose on the streets of San Diego (left), first thoughts were of girls and bright lights. But this (center) is as close as these two would get to anything feminine. In reality, the highlight of most Boot-Camp liberties was the San Diego Zoo (right).

The first navy liberty came after three weeks of training. Turned loose on the streets of San Diego (left), first thoughts were of girls and bright lights. But this (center) is as close as these two would get to anything feminine. In reality, the highlight of most Boot-Camp liberties was the San Diego Zoo (right).

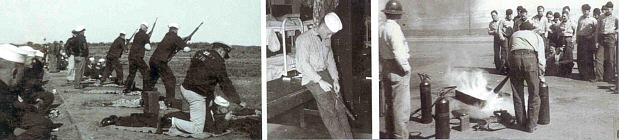

As training continued, the emphasis shifted from basic personal habits to perfecting skills needed to perform naval duties. Time was spent on the firing range at Camp Elliott (left) as well as at the Damage Control facility on Coronado Island (right). And there was also the matter of learning to stay awake during a mid watch (midnight to 4 AM). It would appear here (center) that Hobson has not yet developed that ability.

As training continued, the emphasis shifted from basic personal habits to perfecting skills needed to perform naval duties. Time was spent on the firing range at Camp Elliott (left) as well as at the Damage Control facility on Coronado Island (right). And there was also the matter of learning to stay awake during a mid watch (midnight to 4 AM). It would appear here (center) that Hobson has not yet developed that ability.

Mail Call was the highlight of any day there was a delivery, not only during Boot Camp (left), but throughout all the navy years that followed. As the weeks passed, there was steadily increasing proficiency in performance of standard naval procedures, like bag inspections (center). During their seemingly endless marching drills, Company 614 progressed from a rag-tag assemblage to a distinguished performance in the Graduation Parade.

Mail Call was the highlight of any day there was a delivery, not only during Boot Camp (left), but throughout all the navy years that followed. As the weeks passed, there was steadily increasing proficiency in performance of standard naval procedures, like bag inspections (center). During their seemingly endless marching drills, Company 614 progressed from a rag-tag assemblage to a distinguished performance in the Graduation Parade.

With Boot-Camp training now history, the sailors of Company 614 prepared to leave for their next duty stations. Over half of Companies 613 thru 615, including the four sailors from Ventura, were assigned to the heavy cruiser U. S. S. Rochester, at that time undergoing a major overhaul at Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Northern California. (Romig had requested submarine duty, but was ignored.) In the photo below left, they wait for busses that will carry them to the San Diego railroad station.

With Boot-Camp training now history, the sailors of Company 614 prepared to leave for their next duty stations. Over half of Companies 613 thru 615, including the four sailors from Ventura, were assigned to the heavy cruiser U. S. S. Rochester, at that time undergoing a major overhaul at Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Northern California. (Romig had requested submarine duty, but was ignored.) In the photo below left, they wait for busses that will carry them to the San Diego railroad station.

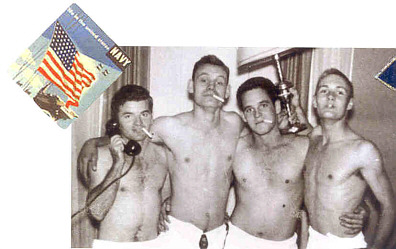

The train ride north to Richmond, across the Bay from San Francisco, was made in ancient railroad cars and seemed to take forever. Above right (l-r), Hobson, Moore, Cox and Romig settled in for the long journey. It was obvious that the railroad had given this train very low priority, and the trip took over 24 hours! Whenever another train approached, either passenger or freight, the Navy train was always the one shunted to a siding until the other had passed. It began to appear that the Korean war would end before this bunch reached their ship! When the train finally crept into Richmond, they transferred to a fleet of buses that carried them northward along the edge of the Bay to the Mare Island Shipyard. It was March 4th, 1951.

Real Sailors at Last

Their destination, U.S.S. ROCHESTER CA-124, had recently returned from action in the Korean war. When their orders were read to them that last day at Boot Camp, the Chief Petty Officer making the announcement had remarked, “the Rochester, now that’s a real fightin’ ship!”

Their destination, U.S.S. ROCHESTER CA-124, had recently returned from action in the Korean war. When their orders were read to them that last day at Boot Camp, the Chief Petty Officer making the announcement had remarked, “the Rochester, now that’s a real fightin’ ship!”

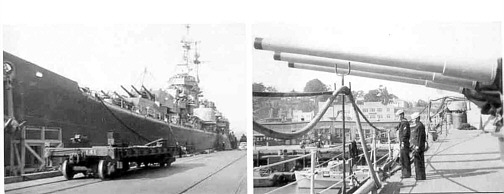

Above left is ROCHESTER at Pier 21, Mare Island Naval Shipyard. This was the destination of the busses that carried the sailors from the railroad station in Richmond. Upon their arrival, the buses stopped at the foot of the gangway and the sailors ascended to their new home. Above right, Hobson and Cox explore an unfamiliar setting.

Above left is ROCHESTER at Pier 21, Mare Island Naval Shipyard. This was the destination of the busses that carried the sailors from the railroad station in Richmond. Upon their arrival, the buses stopped at the foot of the gangway and the sailors ascended to their new home. Above right, Hobson and Cox explore an unfamiliar setting.

Each of the four sailors from Ventura had until this time experienced identical training, but once in ROCHESTER they went separarate ways. Cox opted for Storekeeper in S1 Div., Moore for Firecontrolman in Fox Div., Hobson for Quartermaster in N Div. (after a detour through Fox Div.) and Romig for Boatswain’s Mate in 5th Div.

Each of the four sailors from Ventura had until this time experienced identical training, but once in ROCHESTER they went separarate ways. Cox opted for Storekeeper in S1 Div., Moore for Firecontrolman in Fox Div., Hobson for Quartermaster in N Div. (after a detour through Fox Div.) and Romig for Boatswain’s Mate in 5th Div.

Romig submitted another request for submarine duty and this time there was a response: such a request would not be considered, he was informed, until after he had served 12 months!

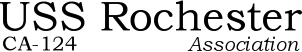

Most shipyard tasks were tedious at best, although putting paint on, as below left, was much preferable to chipping paint off. Either way, chores like these increased anticipation of getting ashore at workday’s end. Generally this meant crossing the channel to Vallejo, which at that time was very much a Navy town. But options during liberty in downtown Vallejo were limited, as Moore, Hobson and Romig are discovering below, center. They quickly learned that to make the most of their time ashore, Romig had to get his car. So on a weekend liberty he flew home–his first experience in a commercial airplane.

Although each had taken a different direction in shipboard duties, they continued to join up for liberty. On the left, Moore and Hobson emerge from the Mare Island ship’s store with the makings of a lively time ashore. They shift to civilian duds in Romig’s car, parked in an alley in downtown Vallejo, and are ready for the night ahead. Then, with Cox and some friendly local girls, they headed for a party in the hills above Oakland.

Although each had taken a different direction in shipboard duties, they continued to join up for liberty. On the left, Moore and Hobson emerge from the Mare Island ship’s store with the makings of a lively time ashore. They shift to civilian duds in Romig’s car, parked in an alley in downtown Vallejo, and are ready for the night ahead. Then, with Cox and some friendly local girls, they headed for a party in the hills above Oakland.

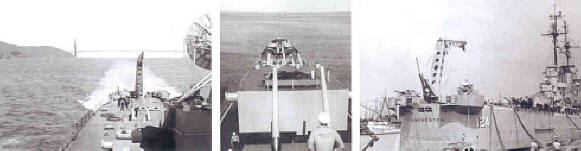

Late in May, her 3-month overhaul completed, ROCHESTER steamed out through the Golden Gate and headed south. She passed Point Conception, entered a tranquil sea off Southern California, and finally docked at the Long Beach Naval Shipyard. This was to be her home port during the months of training that lay ahead.

Late in May, her 3-month overhaul completed, ROCHESTER steamed out through the Golden Gate and headed south. She passed Point Conception, entered a tranquil sea off Southern California, and finally docked at the Long Beach Naval Shipyard. This was to be her home port during the months of training that lay ahead.

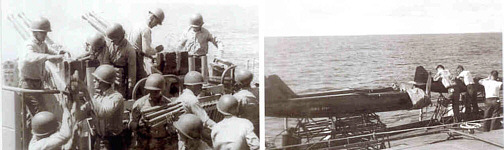

The weeks that followed involved training for the anticipated return to Korea. There was emphasis on simulated air attacks, probably because during her previous Korean action ROCHESTER had been struck by a bomb dropped from an enemy aircraft that had swooped in undetected. Fortunately, that bomb glanced off the crane without exploding, but a possible next one could be a direct hit and deadly. In the series of photos below, the secondary batteries are firing at remote-controlled drones launched from deck.

The weeks that followed involved training for the anticipated return to Korea. There was emphasis on simulated air attacks, probably because during her previous Korean action ROCHESTER had been struck by a bomb dropped from an enemy aircraft that had swooped in undetected. Fortunately, that bomb glanced off the crane without exploding, but a possible next one could be a direct hit and deadly. In the series of photos below, the secondary batteries are firing at remote-controlled drones launched from deck.

A routine developed that had ROCHESTER at sea from Monday to Friday, and in port during the weekends–usually in Long Beach, but sometimes in San Diego.

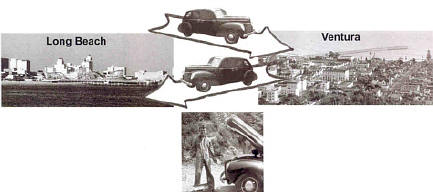

With Ventura just a 3-hr drive from Long Beach, Romig’s car burned up Pacific-Coast Highway during just about every 48-hr and 72-hr weekend liberty. But while 3 hrs was the normal time for this trip, with the age of Romig’s car it often took longer to get there. (This was before the freeways had been constructed. Today it can take much less or even more time, depending on the traffic.)

With Ventura just a 3-hr drive from Long Beach, Romig’s car burned up Pacific-Coast Highway during just about every 48-hr and 72-hr weekend liberty. But while 3 hrs was the normal time for this trip, with the age of Romig’s car it often took longer to get there. (This was before the freeways had been constructed. Today it can take much less or even more time, depending on the traffic.)

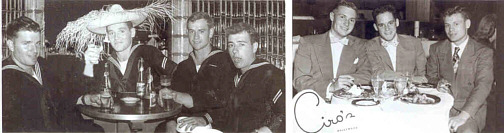

When weekend liberties were limited to Friday night, they had to stay closer to the ship. One Friday night when ROCHESTER was spending the weekend in San Diego they visited their first foreign port-of-call–Tijuana, in Old Mexico. At left, Cox and Hobson enjoy a round of cerveza with Jim Flot (Fox Div.) and Hellyer (S1 Div.). When ROCHESTER spent the weekend in Long Beach, a single night ashore was enough time to experience the high life of Los Angeles or Hollywood, as Moore, Hobson and Romig are doing on the right.

When weekend liberties were limited to Friday night, they had to stay closer to the ship. One Friday night when ROCHESTER was spending the weekend in San Diego they visited their first foreign port-of-call–Tijuana, in Old Mexico. At left, Cox and Hobson enjoy a round of cerveza with Jim Flot (Fox Div.) and Hellyer (S1 Div.). When ROCHESTER spent the weekend in Long Beach, a single night ashore was enough time to experience the high life of Los Angeles or Hollywood, as Moore, Hobson and Romig are doing on the right.

With the advance of summer, action by ROCHESTER’s gunners, as by the 40 mm crew above, became less frequent, and the target drones spent more days resting idly on deck. The navy was learning something long-known to at least those ROCHESTER sailors that had grown up on southern California beaches; that is, one can expect heavy overcast along the coast at this time of year. As a result, ROCHESTER’s gunners were getting insufficient training–and she was scheduled to return to the war in Korea in a few months.

With the advance of summer, action by ROCHESTER’s gunners, as by the 40 mm crew above, became less frequent, and the target drones spent more days resting idly on deck. The navy was learning something long-known to at least those ROCHESTER sailors that had grown up on southern California beaches; that is, one can expect heavy overcast along the coast at this time of year. As a result, ROCHESTER’s gunners were getting insufficient training–and she was scheduled to return to the war in Korea in a few months.

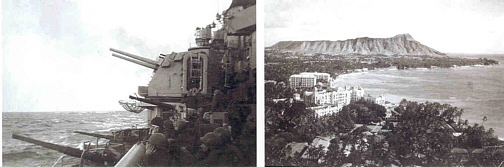

The solution to gaining the needed training: shift operations to the predictably clear skies of the Hawaiian Islands. While perhaps not all hands were pleased with this development, the 4 sailors from Ventura were ecstatic! So when on 27 August 1951 ROCHESTER steamed out of Long Beach harbor (left), she did not turn north or south, as had been the usual procedure for so many weeks. This time she continued westward, and 5 days later the island of Oahu appeared under clouds off the starboard bow. A short time later, Hobson and Moore were photographed with Diamond Head as a background.

Hula dancers welcomed ROCHESTER as she docked at Pearl Harbor, and shortly after the gangway was set in place, Romig, Moore and Hobson were ashore, rarin’ to go (although they don’t look too lively in this photo). They were up a tree a few hours later (with Don Shortreed, Fox Div.), but despite a valiant effort never got high enough to pick coconuts.

Hula dancers welcomed ROCHESTER as she docked at Pearl Harbor, and shortly after the gangway was set in place, Romig, Moore and Hobson were ashore, rarin’ to go (although they don’t look too lively in this photo). They were up a tree a few hours later (with Don Shortreed, Fox Div.), but despite a valiant effort never got high enough to pick coconuts.

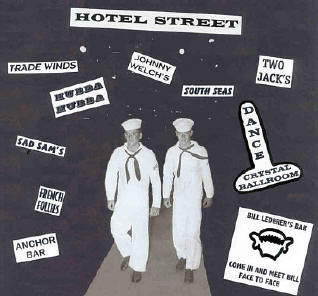

“Dear Mom and Dad, Last night we went to a dance at the Armed Forces YMCA…”

“Dear Mom and Dad, Last night we went to a dance at the Armed Forces YMCA…”

It would have been easy to forget why ROCHESTER had come to the Islands, but a full training schedule kept her at sea most of the time. California’s heavy coastal overcast was replaced by clear Hawaiian skies and the ship’s batteries stayed busy. After almost 50 years, however, most memories of that period are of times ashore. Many of these recollections involve Waikiki Beach, which during the early 1950s (right) was very unlike the Waikiki of today. At that time, just two hotels dominated the scene–the Royal Hawaiian and Moana; today, these two are lost amid a dense sea of much larger structures that tower above them.

It would have been easy to forget why ROCHESTER had come to the Islands, but a full training schedule kept her at sea most of the time. California’s heavy coastal overcast was replaced by clear Hawaiian skies and the ship’s batteries stayed busy. After almost 50 years, however, most memories of that period are of times ashore. Many of these recollections involve Waikiki Beach, which during the early 1950s (right) was very unlike the Waikiki of today. At that time, just two hotels dominated the scene–the Royal Hawaiian and Moana; today, these two are lost amid a dense sea of much larger structures that tower above them.

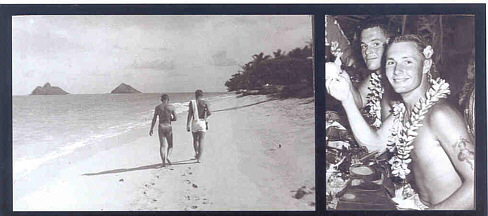

As remembered, walks along a beach of windward Oahu were on a remote tropical shore, and it seems that even a luau in Waikiki was more authentic than it would be today. But were they really?

As remembered, walks along a beach of windward Oahu were on a remote tropical shore, and it seems that even a luau in Waikiki was more authentic than it would be today. But were they really?

The day finally arrived in mid November when the carry-all was loaded aboard, and ROCHESTER steamed out of Pearl Harbor for what would be the last time for over five months. In company with the heavy cruiser ST. PAUL and the battleship WISCONSIN, she was headed for Korea.

The day finally arrived in mid November when the carry-all was loaded aboard, and ROCHESTER steamed out of Pearl Harbor for what would be the last time for over five months. In company with the heavy cruiser ST. PAUL and the battleship WISCONSIN, she was headed for Korea.

The Real Thing

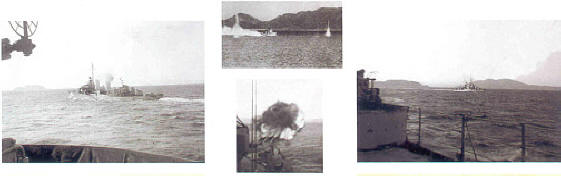

A mid-Pacific storm tested ROCHESTER’s seaworthiness during the voyage to Japan (left). In the center, Fox Div. is at quarters for entering port. At right, ROCHESTER is moored alongside at Yokosuka Naval Shipyard.

A mid-Pacific storm tested ROCHESTER’s seaworthiness during the voyage to Japan (left). In the center, Fox Div. is at quarters for entering port. At right, ROCHESTER is moored alongside at Yokosuka Naval Shipyard.

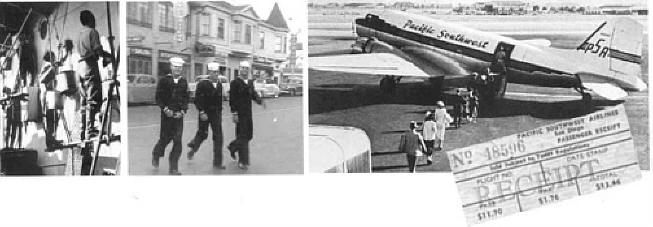

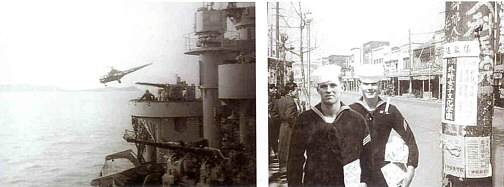

Most Yokosuka liberties began at the Enlisted-men’s Club just outside the base gate (above left, background center), where the surroundings were somewhat familiar. Upon stepping from there onto the streets of the city, however, it was clear they weren’t in Ventura anymore.

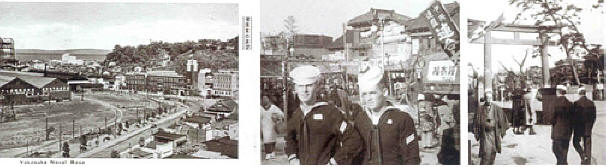

ROCHESTER was in port just a few days–enough time to be readied for her return to action in Korea–but the crew was given every opportunity to get ashore. At left, Jim Flot (Fox Div.) and Hobson are obviously enjoying some Yokosuka hospitality. All too soon, however, the mooring lines were cast off and ROCHESTER steamed out of the harbor. First she headed south, and passed thru Shimonoseki Strait between Honshu and Kyushu (center). That’s ST. PAUL following astern. Then she headed out into the Sea of Japan, encountering some weather as she steamed westward (right).

ROCHESTER was in port just a few days–enough time to be readied for her return to action in Korea–but the crew was given every opportunity to get ashore. At left, Jim Flot (Fox Div.) and Hobson are obviously enjoying some Yokosuka hospitality. All too soon, however, the mooring lines were cast off and ROCHESTER steamed out of the harbor. First she headed south, and passed thru Shimonoseki Strait between Honshu and Kyushu (center). That’s ST. PAUL following astern. Then she headed out into the Sea of Japan, encountering some weather as she steamed westward (right).

By morning, a snow-covered Korean coast was partially visible amid storm clouds. ROCHESTER had joined Task Force 77 during the night and was now on station near the “38th Parallel” (38 degrees north latitude). This is the border between North and South Korea, where action was concentrated during much of the war. That’s the carrier ESSEX (CV-9) across the water.

By morning, a snow-covered Korean coast was partially visible amid storm clouds. ROCHESTER had joined Task Force 77 during the night and was now on station near the “38th Parallel” (38 degrees north latitude). This is the border between North and South Korea, where action was concentrated during much of the war. That’s the carrier ESSEX (CV-9) across the water.

ROCHESTER alternated between steaming with the carriers offshore and operating independently or in company with a destroyer to carry out firing missions along the coast. Frequent targets for such missions were in the area around Kosong, shown under fire below. Kosong is just a short distance north of the 38th Parallel.

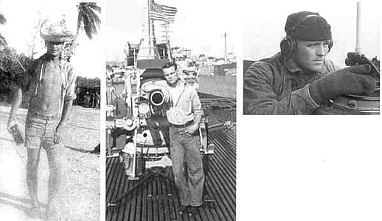

Battle Stations: Romig was one of the crew of a 5″ mount. In the left photo they have emerged for a breath of fresh air (one holds a snowball he had scooped off the deck). Romig is third from the right (in the middle). Moments later Officer of the Deck called down from the bridge wing, ordering them to get inside and seal up the door. Moore (upper center) was ready to direct fire of a 40-mm battery, but enemy targets never got within range. The only firing by the 40’s was in practice. For Hobson to get to his battle station, he had to climb down a ladder (center) into the bowels of the ship. There, in a tiny compartment above the rudder (designated “After Steering”), he stood ready to steer the ship in the event battle damage took out the regular steering system on the bridge. This might have been a good place to avoid superficial damage topside, but there could not have been a worse place to be if the ship sank!

Cox’s battle station was as crewman of a 40-mm battery (left), which, like the mount directed by Moore, never fired a shot at the enemy. Although fresh air could be an asset of battle stations topside, not under conditions frequently encountered during the long Korean winter.

Cox’s battle station was as crewman of a 40-mm battery (left), which, like the mount directed by Moore, never fired a shot at the enemy. Although fresh air could be an asset of battle stations topside, not under conditions frequently encountered during the long Korean winter.

Because ROCHESTER steamed day and night, there was a regular need for refueling. Below left, an oiler comes alongside to transfer fuel, while, below right, Romig seems in need of help with the fuel lines. About this time, he completed the stipulated 12 months in service and once again requested submarine duty.

Because ROCHESTER steamed day and night, there was a regular need for refueling. Below left, an oiler comes alongside to transfer fuel, while, below right, Romig seems in need of help with the fuel lines. About this time, he completed the stipulated 12 months in service and once again requested submarine duty.

Most of ROCHESTER’S missions involved her main battery of 8″ gun’s. Targets included railroads, bridges, and troop concentrations at distances of up to 12 or 13 miles. Because of Korea’s mountainous interior, most major lines of transportation were along the coast, and therefore within range of ROCHESTER’s guns. Much of this fire was directed by spotters aloft in the ship’s helicopter, shown below returning from such a mission. Another of the helicopter’s vital functions was rescue of downed aviators. The much-decorated pilot of ROCHESTER’s helicopter, CPO Duane Thorin, made more than 130 rescues and evacuations from enemy territory. And helicopter crewman Ernie Crawford was awarded the Navy Cross for heroic action during one rescue at sea. That the helicopter was itself at times a target is shown by the bullet hole being inspected here by R. Gibson of Fox Division. This damage proved prophetic, as during February the helicopter was downed during a rescue attempt near Wonsan, and Chief Thorin spent the rest of the war in a POW camp. (See Earl Lanning’s tribute to Thorin and Crawford, “Not Heroes, Just Good Sailors.”)

Most of ROCHESTER’S missions involved her main battery of 8″ gun’s. Targets included railroads, bridges, and troop concentrations at distances of up to 12 or 13 miles. Because of Korea’s mountainous interior, most major lines of transportation were along the coast, and therefore within range of ROCHESTER’s guns. Much of this fire was directed by spotters aloft in the ship’s helicopter, shown below returning from such a mission. Another of the helicopter’s vital functions was rescue of downed aviators. The much-decorated pilot of ROCHESTER’s helicopter, CPO Duane Thorin, made more than 130 rescues and evacuations from enemy territory. And helicopter crewman Ernie Crawford was awarded the Navy Cross for heroic action during one rescue at sea. That the helicopter was itself at times a target is shown by the bullet hole being inspected here by R. Gibson of Fox Division. This damage proved prophetic, as during February the helicopter was downed during a rescue attempt near Wonsan, and Chief Thorin spent the rest of the war in a POW camp. (See Earl Lanning’s tribute to Thorin and Crawford, “Not Heroes, Just Good Sailors.”)

ROCHESTER’S varied missions often took her far north behind enemy lines. Raids on Wonsan Harbor required traversing Wonsan Narrows, a mine-infested channel between several islands and headlands. On the left, ROCHESTER heads into the channel accompanied by the destroyer O’BANNON. Red gunners on hills overlooking the channel normally declined to fire on ROCHESTER, apparently fearing retaliation from her big guns, but they frequently fired on minesweepers that worked to clear the channel of mines (upper center). ROCHESTER opened the attack with a three-gun salvo from her forward main battery as she steamed into the harbor at full speed (lower center). Once inside, the attacking warships zeroed in on a variety of targets, the prime one being a railroad junction. On the right, ROCHESTER and destroyer HIGBEE, their mission completed, steam out through the Narrows toward the open sea.

ROCHESTER’S varied missions often took her far north behind enemy lines. Raids on Wonsan Harbor required traversing Wonsan Narrows, a mine-infested channel between several islands and headlands. On the left, ROCHESTER heads into the channel accompanied by the destroyer O’BANNON. Red gunners on hills overlooking the channel normally declined to fire on ROCHESTER, apparently fearing retaliation from her big guns, but they frequently fired on minesweepers that worked to clear the channel of mines (upper center). ROCHESTER opened the attack with a three-gun salvo from her forward main battery as she steamed into the harbor at full speed (lower center). Once inside, the attacking warships zeroed in on a variety of targets, the prime one being a railroad junction. On the right, ROCHESTER and destroyer HIGBEE, their mission completed, steam out through the Narrows toward the open sea.

At the rate ROCHESTER was sending projectiles at targets ashore, she needed to be frequently re-supplied with ammunition. And it was more of a chore bringing ammunition aboard than it was in sending it shoreward. Often combined with the transfer of ammunition and other supplies was the transfer of mail–not only for ROCHESTER, but also for other ships in the area. So after the AKA shown above had delivered ammo (and mail) and steamed away, destroyer ERBEN pulled up to receive a bag of mail addressed to her crew. For most, letters from home were more important than the ship being re-supplied with fuel and ammunition.

At the rate ROCHESTER was sending projectiles at targets ashore, she needed to be frequently re-supplied with ammunition. And it was more of a chore bringing ammunition aboard than it was in sending it shoreward. Often combined with the transfer of ammunition and other supplies was the transfer of mail–not only for ROCHESTER, but also for other ships in the area. So after the AKA shown above had delivered ammo (and mail) and steamed away, destroyer ERBEN pulled up to receive a bag of mail addressed to her crew. For most, letters from home were more important than the ship being re-supplied with fuel and ammunition.

ROCHESTER alternated periods of three to four weeks in the war zone with a week or so in Yokosuka (once Sasebo). Gifts for the folks and others back home became major objectives of liberty in Japan, where a seaman’s pay could be stretched much farther than in the States.

ROCHESTER alternated periods of three to four weeks in the war zone with a week or so in Yokosuka (once Sasebo). Gifts for the folks and others back home became major objectives of liberty in Japan, where a seaman’s pay could be stretched much farther than in the States.

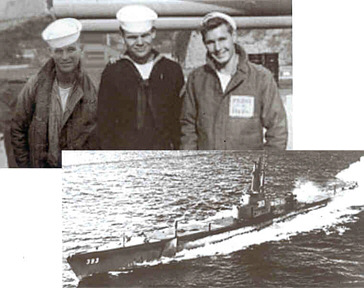

Romig’s repeated requests for submarine duty finally paid off, as in late February he received orders to report to U.S.S. QUEENFISH at Pearl Harbor. In the upper photo, flanked by Hobson and Moore, he is about to leave ROCHESTER at Yokosuka for his new assignment. He had been set to take the exam for Boatswain’s Mate 3c before the transfer came through, and only after reporting to QUEENFISH did he learn there are no Boatswain’s Mates in submarines. Thus began his career as a Gunner’s Mate.

Romig’s repeated requests for submarine duty finally paid off, as in late February he received orders to report to U.S.S. QUEENFISH at Pearl Harbor. In the upper photo, flanked by Hobson and Moore, he is about to leave ROCHESTER at Yokosuka for his new assignment. He had been set to take the exam for Boatswain’s Mate 3c before the transfer came through, and only after reporting to QUEENFISH did he learn there are no Boatswain’s Mates in submarines. Thus began his career as a Gunner’s Mate.

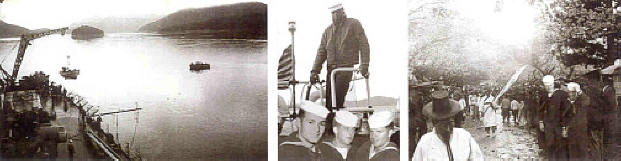

The only opportunity that most ROCHESTER sailors had to set foot on Korean soil was during a March visit to Chinhae, on the southern coast. The launch was lowered into the water shortly after the ship dropped anchor, and soon was ferrying the liberty party to the beach. The launch’s coxswain was R. L. Fears (2nd Div.), and among the passengers were the three remaining sailors from Ventura. They stepped on shore to find the cherry blossoms in full bloom, a clear sign that spring had arrived and that they were now short-timers in WestPac.

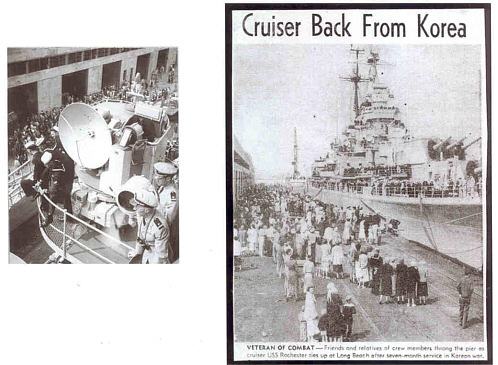

On 21 April, JUNEAU arrived at Yokosuka to relieve ROCHESTER in WestPac. Within hours, ROCHESTER was headed eastward across the Pacific, sometimes at flank speed. After a brief stop at Pearl Harbor, she continued on to finally pass through the Long Beach breakwater and arrive home.

On 21 April, JUNEAU arrived at Yokosuka to relieve ROCHESTER in WestPac. Within hours, ROCHESTER was headed eastward across the Pacific, sometimes at flank speed. After a brief stop at Pearl Harbor, she continued on to finally pass through the Long Beach breakwater and arrive home.

ROCHESTER came alongside the wharf at Long Beach to complete her second tour of war duty. With the experience they had gained, the four from Ventura were confident they had completed the transition from civilian to sailor. ROCHESTER would have two more cruises to the far east during their enlistments (see “A Winter in Westpac” and “To Show the Flag”), but of the original four, only Cox and Hobson would be on board.

ROCHESTER came alongside the wharf at Long Beach to complete her second tour of war duty. With the experience they had gained, the four from Ventura were confident they had completed the transition from civilian to sailor. ROCHESTER would have two more cruises to the far east during their enlistments (see “A Winter in Westpac” and “To Show the Flag”), but of the original four, only Cox and Hobson would be on board.

Moore transferred to shore duty on the Island of Saipan (left) before ROCHESTER’s next tour in WestPac. (Did he do this for the more casual uniform code there?) Meanwhile, Romig thrived in QUEENFISH. Six months after reporting aboard he pinned on his submariner’s dolphins and a month later advanced to Gunner’s Mate 3c. Hobson’s action station during subsequent operations in ROCHESTER was on the bridge, where he took bearings of charted objects ashore for the Navigator. Not only was this more interesting than his previous station in After Steering, now he could see where he was going.

Moore transferred to shore duty on the Island of Saipan (left) before ROCHESTER’s next tour in WestPac. (Did he do this for the more casual uniform code there?) Meanwhile, Romig thrived in QUEENFISH. Six months after reporting aboard he pinned on his submariner’s dolphins and a month later advanced to Gunner’s Mate 3c. Hobson’s action station during subsequent operations in ROCHESTER was on the bridge, where he took bearings of charted objects ashore for the Navigator. Not only was this more interesting than his previous station in After Steering, now he could see where he was going.

Aside from these brief notes, events during the 2.5 years following that first tour in Korea are beyond the scope of this account. The four from Ventura had become seasoned sailors.

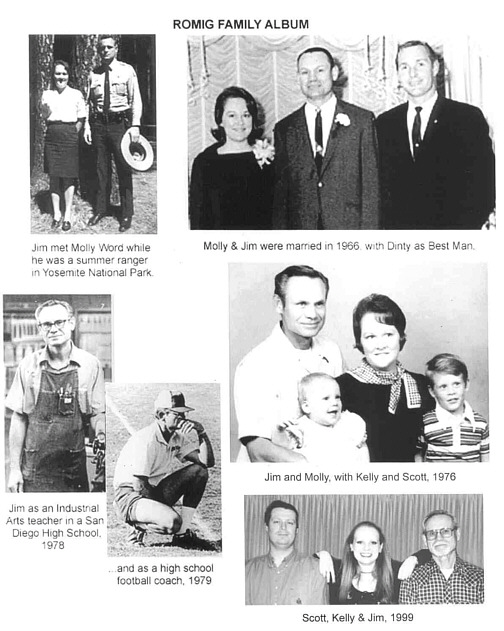

The day finally arrived–12 October, 1954–when the Plan Of The Day listed Cox and Hobson among those to be transferred for separation. ROCHESTER was at a mooring inside the breakwater at Long Beach, and the separation was to be at the nearby shipyard. So the transfer involved just a short run in the ship’s launch. In the two photos on the left, they have discharge papers in hand and have been civilians for about 30 minutes. Next to them is Hobson’s car, in which they will drive to Ventura. On the right, two weeks later, Romig and Moore–civilians for less than a week–have joined Hobson to celebrate their reunion at the large concrete “V” on the hillside above town. This was to be the last time that the three of them would ever be together.

The day finally arrived–12 October, 1954–when the Plan Of The Day listed Cox and Hobson among those to be transferred for separation. ROCHESTER was at a mooring inside the breakwater at Long Beach, and the separation was to be at the nearby shipyard. So the transfer involved just a short run in the ship’s launch. In the two photos on the left, they have discharge papers in hand and have been civilians for about 30 minutes. Next to them is Hobson’s car, in which they will drive to Ventura. On the right, two weeks later, Romig and Moore–civilians for less than a week–have joined Hobson to celebrate their reunion at the large concrete “V” on the hillside above town. This was to be the last time that the three of them would ever be together.

The Rest of the Story

JIM ROMIG

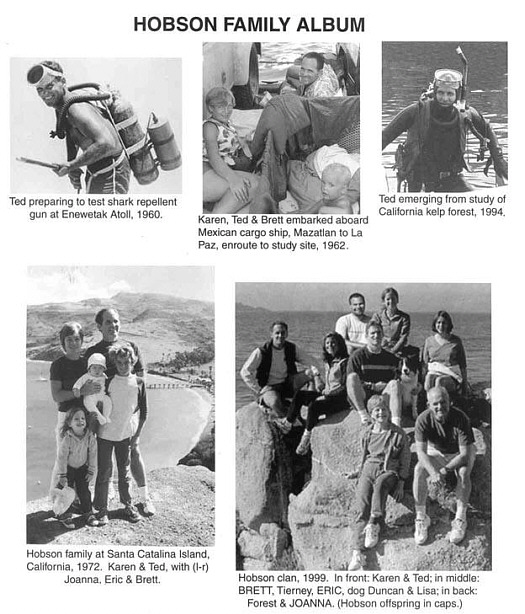

Jim Romig, Gunner’s Mate 2c (SS), was discharged from the Navy at Treasure Island, California, on 28 October 1954. In the spring of 1955, he enrolled at Ventura Junior College, where his play at linebacker on the football team earned him a scholarship to San Diego State University. He entered SDSU during the fall of 1956, and after three years of study and football graduated in the spring of 1959 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Industrial Arts and Physical Education. An additional year of study earned him a Teaching Credential and a job with the San Diego School District. He spent over 20 years with the District, teaching Industrial Arts and coaching high-school football. Along the way (1964), he earned a Master’s Degree at SDSU. Then in 1981 he transferred to the Grossmont-Cuymaca Community College District and finished his career with over 12 years at Cuymaca College as a teacher of welding and physical education. He retired in 1993.

During his early years as a teacher, Jim worked each summer (1962-1971) as a Ranger in Yosemite National Park, and there met Molly Word, who was secretary for the Park’s Chief Ranger. Jim and Molly were married in 1966 and have two children, a son Scott, born in 1971 (in the Yosemite Park Hospital), and a daughter Kelly, born in 1974. Molly died of cancer in 1994.

Jim now spends most of his time in San Diego, frequently visiting with Scott and Kelly, who live nearby. For two to three months of each year, however, he takes to the road in his one-ton Dodge diesel dually with camper. He stays with his brother in Texas for a month or so, then heads out to investigate features of the country he served in that war so long ago. During his travels he also visits old friends now widely scattered across the country, many of them Navy shipmates.

TED HOBSON

The day after his final reunion with Romig and Moore on the hill overlooking Ventura, Ted headed east to investigate an invitation to play football at the College of William and Mary, in Virginia. His discussions with the coach went well, but there was a hitch. Before joining the team, he had to be accepted as a student, and upon reviewing his academic record the College Administration informed him that this would happen only after he had demonstrated an ability to perform successfully in the classroom. They suggested he do this at an extension of the college in Norfolk, where entrance requirements were more lenient. If successful there, he was told, admission to the main campus and the football team would follow. But even the Norfolk Division balked upon reviewing his transcript of grades, and only reluctantly did they allow him to take a general aptitude test. To their surprise, however, he scored high on the test and so was admitted for the 1955 spring semester.

If the college was surprised at the high test score, Ted was even more surprised by how much he enjoyed his classes. Furthermore, the exposure to formal instruction in biology rekindled an interest in tropical marine fishes that he had developed years earlier while living in Florida. This interest continued to grow until all desire to play football was gone and he aspired only to be an ichthyologist. So upon completing the curriculum in Norfolk during the spring of 1956, he applied for admission, not to the main campus of William and Mary, but to the University of Hawaii.

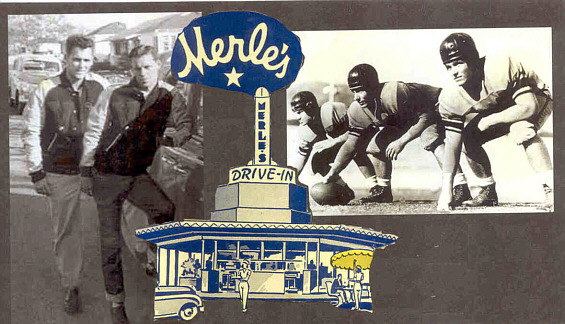

Once in Hawaii, Ted took off on a course that could not have been predicted just a few years before. After receiving a Bachelor of Arts degree in June 1958, he continued there during the following fall in the Graduate School. He had acquired expertise in the new sport of scuba diving, using it in several class projects as an undergraduate, and this became his primary research tool as a graduate student. The research for his Masters thesis–a study of shark behavior in the lagoon of a western Pacific atoll–was the basis of the Master of Science degree awarded to him in the spring of 1961. During this period, he met (1958), and married (1959), his wife Karen, and they were joined by their first son Brett (1960).

Now on a roll, the Hobson family moved to California during the fall of 1961, and Ted enrolled as a candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree at UCLA. The Hobsons spent much of the next four years in Baja California Sur, Mexico, where Ted’s dissertation research involved study of predatory behavior in fishes of the Gulf of California. As in his earlier studies, Ted based this work on underwater observations of the fishes in their natural environment. He received his PhD in Ichthyology during 1967, and then began a long career as a marine biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

All three Hobson children lived virtually at the water’s edge during their most formative years, ages 1-4: Brett (b. 1960) during the Gulf of California study (1962-1965), Joanna (b. 1968) during study of coral-reef fishes at Kona, Hawaii (1969-1970) and Eric (b.1972) during study of kelp-forest fishes at Santa Catalina Island, California (1972-1975). Nocturnal behavior was a major part of these investigations, so the Hobson household was involved 24 hrs a day. With this intimate exposure to the marine environment during development of so many basic personality traits, it is not surprising that at present all three offspring are in ocean-related professions.

Ted is still going strong after over 40 years of scuba-based research (although in an emeritus role since December 2000, as far as NOAA is concerned). He occasionally reminisces, and in looking back recognizes that events would have taken a radically different course had not an appreciation for academics surfaced when he returned to school after his time in the Service. He attributes this to a sense of values gained in the Navy, which poses the question: What if North Korea had not invaded the South during the summer of 1950…..?

DINTY MOORE

Dinty remained in Ventura for several years after his discharge from the Navy. He married his on-again/off-again girlfriend, Gail McAndrews, and in 1956 they had a son, Clifford. But the marriage ended with a divorce in about 1960. Dinty then moved to Reno, Nevada, and began a long career in construction that was to include the building of most of that city’s well-known casinos. With the Sierra-Nevada mountains nearby, he became an avid outdoors man. On his way home from work in the evening, it became routine that he would stop to fish in the Truckee River, which flows through Reno.

He married Judy during the mid 1960s, and over the next several years they had three daughters–Dawn, Lisa and Dana. That marriage proved no more lasting than his first, however, ending with a divorce in about 1970. But within a few years he had met and then married Erma, and this time settled into a long and satisfying relationship. Although Dinty and Erma had no children together, he adopted Erma’s daughter, Kelly.

Dinty was County Building Inspector during his later years, and in this capacity became involved in every major construction project at a time that Reno was experiencing explosive growth. He also reconnected with his son Cliff, and a warm bond developed between them. Dinty had finally found contentment when–suddenly and unexpectedly–his life ended at age 53 with a stroke in December,1985.

There is a remembrance of Dinty Moore, written by Hobson, in the Taps section:

ART COX

Richard A. “Art” Cox married Elaine Kolkman of Ventura (literally the girl next door) on 19 September, 1954–a month before his discharge from the Navy. They settled in Ventura, where Art’s first job was as salesman for Jewel Tea Company. Elaine had studied nursing after she and Art graduated together from Ventura high school, and upon gaining her degree began a 30-yr career as a Surgical Nurse with Ventura’s Community Memorial Hospital.

Art put his Navy specialty to use in 1959, when he purchased a Mexican fast-food restaurant on Main Street in downtown Ventura. This establishment, close to Ventura High School, was for 17 years a favored hang-out for students. Art sold it in 1976, however, and took a position with the U. S. Postal Service in nearby Oxnard. He retired in 1991.

Art and Elaine have two sons, Richard (Rick) Jr. and Larry. They also have a daughter, Karen. All three now have families of their own, and have provided Art and Elaine with seven grandchildren (including twin girls). The entire clan live in Ventura, so family barbecues are frequent.

Art and Elaine have traveled extensively during their retirement years. They have crossed the U. S. and Baja California in a motor home, and have been to sea on a number of cruises. When at home, Art plays golf, bowls and also plays cribbage, while Elaine loves to crochet, knit and solve cross-word puzzles. Both continue to enjoy good health, and find particular pleasure in attending their grandchildren’s school functions. They are consummate grandparents.